ETHICAL REPORTING

MINIMIZES HARM

Caution tape often marks both a physical boundary and the ethical line journalists must navigate when covering traumatic events. //Photograph by Hollyann Presiel

When breaking news hits, reporters often have to weigh the demands of their conscience and doing what’s right, ethically and morally, against the demands of the industry.

Brady Halbleib, a news anchor and reporter for CBS News Sacramento, recalled the stories that lingered most; the moments that stayed with him long after the live shot had ended.

One of those moments happened in January 2024, after his night crew heard a sudden car crash come through the police scanner. It was only 10 minutes from the station, on Capitol Boulevard in Sacramento.

Halbleib and his cameraman arrived first.

They found a dark city street at 10 p.m. and a grey sedan was split completely in half, one piece wrapped around a tree. The engine pushed into the middle of the road and debris was everywhere. The suspected cause: a driver going more than 100 mph, possibly impaired by alcohol or drugs. They seem to have blown through an intersection, struck another vehicle, and then slammed into a tree.

“We couldn’t show anything with the car crash because there was so much,” Halbleib says. “It was too graphic.

There is far more to journalism than many people realize, or give journalists credit for, such as the emotional toll and ethical dilemmas that reporters face. Audiences may forget that reporters are also people who experience harassment and verbal assault from bystanders, both of which may even sometimes lead to physical attacks.

What’s more, research shows post-traumatic stress disorder can affect not only war correspondents but also local reporters covering violence and trauma. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists’ Journalist Security Guide, more than one in eight journalists working in the United States and Europe sampled at large in a 2001 study by the German scholars Teegen and Grotwinkel showed the ongoing signs of extreme stress or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“I don’t think reporters realize what they sign up for with this job,” says Halbleib. “They expect to cover city council meetings and cool stories, but there are also times where you cover really awful situations.”

That crash was not the only moment that tested Halbleib’s boundaries.

Nearly two years earlier, in April 2022, while working in Tulsa, Okla. as a multimedia journalist and fill-in anchor for Channel 2, KJRH, an NBC affiliate, he found himself in a situation that tested his ethical boundaries even more intensely.

It was a homicide reported through the police scanner. Every station responded: Fox 23, Channel 6, Channel 8, and Halbleib’s own newsroom.

When he arrived with his photographer, he stood with other reporters about 20 feet from the victim: a young man in his 20s who had been shot in the head.

Shortly afterward, the victim’s mother, grandmother and aunts arrived at the scene.

“They went absolutely ballistic,” he says.

Officers held them back as they collapsed into grief, screaming and crying.

Then, in his earpiece, Halbleib heard: “Forty-five seconds out.”

“We did everything that we were supposed to be doing,” he says. “We didn’t show the body. We stayed behind the tape. We used careful language.”

But, he was still uneasy. “It did not feel good in my heart. I did not like it at all.”

Then came the moment he describes as his breaking point: his news director demanded he get a sound bite from the mother.

“That’s where I drew the line. I said, ‘No. I’m not doing it. You can get another reporter. You can fire me.’”

Refusing the interview was the only humane choice he could make, says Halbleib, one that prioritized the mother’s grief over the demands of the live broadcast.

They still went live — every station did — but he did not attempt the interview and luckily wasn’t fired after all.

Amanda Crawford is a University of Connecticut journalism professor and veteran political reporter who has covered the Tucson shooting of Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, and the Aurora theater shooting. She has also researched the political aftermath of Sandy Hook.

Crawford studies how misinformation and damaging media practices evolve around mass shootings, and why guilt, not trauma, is often what haunts journalists most. She argues that modern newsrooms often overlook the harm they inflict during traumatic events.

After seeing “six acres of media trucks crowded a small community,” Crawford says the first ethical question was simple: “Do we need to be sending this many people?”

She argues that the industry often focuses on journalists’ pain before considering how poorly newsrooms cover the trauma of the people in the story. The practices that harm journalists, she explains, are often the same practices that harm victims: flying reporters across the country overnight, sending them into stakeouts, and lining them up to interview people who have already spoken to half a dozen news crews that day.

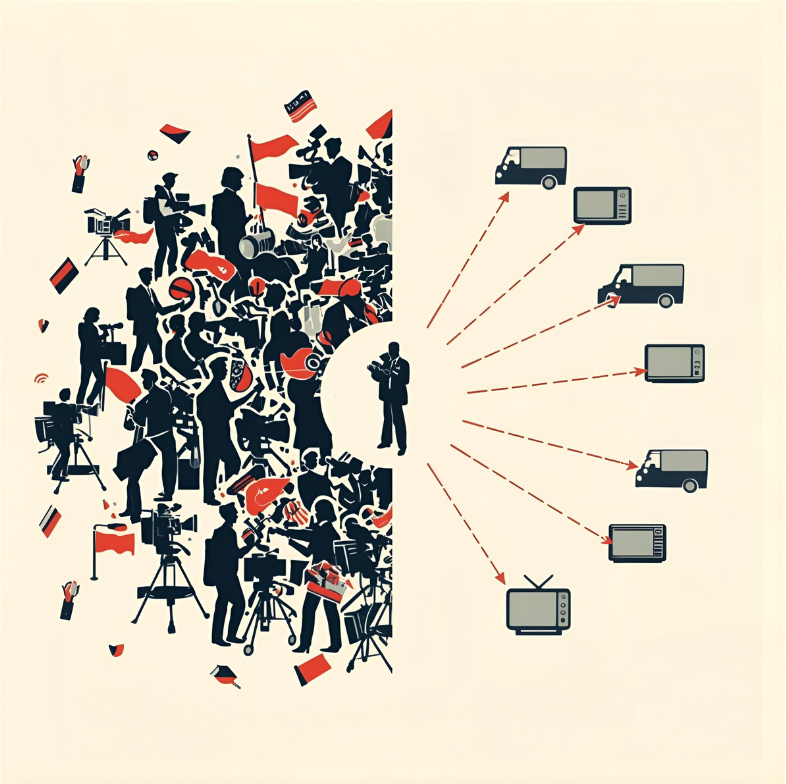

That cycle breeds guilt. Crawford cites The Trauma Beat by Tamara Cherry, published in 2023, noting that the guilt journalists feel after covering mass shootings is often greater than the trauma of witnessing the aftermath of the event itself. That guilt grows out of the media frenzy surrounding these events, an environment she says newsrooms have accepted for decades. She suggests pool reporting, whereby one outlet reports on the scene and shares the broadcast as a way to minimize harm.

Graphic representing pool reporting.// Created by Hollyann Preisel using Canva Magic Media tool

For Tania Lopez, director of communications for Suffolk County District Attorney Ray Tierney and a former Newsday reporter, minimizing harm is essential to ethical journalism.

“Just because you’re a journalist doesn’t mean you’re entitled to someone’s pain,” she says. “It’s a privilege when they share their story with you, and you have an obligation to protect them.”

Protecting identities is not about shielding defendants, it’s about protecting victims, she says.

Amanda Crawford of the University of Connecticut also points to organizations trying to reduce the burden on grieving families. She describes a Boston-based nonprofit called Survivors Say, founded by former broadcast journalist David Guarino. The group sends volunteer public relations professionals to help families navigate media attention after high-profile crimes. The volunteers act as a buffer, coordinating with the press so families don’t have to, while they are still in shock.

Her push for smarter, more restrained coverage speaks to a deeper reality in journalism: different stories require different levels of ethical judgment.

Michael Crowley, a photographer and retired newsroom specialist, learns this early in his career, as even the simplest assignments test him in unexpected ways.

Media community and camaraderie at press conference held at Suffolk County Sheriff's Office, Riverhead Correctional Facility, N.Y. // Photo by Hollyann Preisel

The simple stories, he says, are what he calls the “one-stop-shop” stories — the kind where everything you need is right in front of you. For example, he refers to scenes where the story unfolds plainly, without layers of politics or competing agendas, such as a house fire or car accident.

Crowley recalled one of those moments early in his career at WLIG-TV 55 in Riverhead, New York, when he was assigned a Father’s Day feature. It was 1991, just months after his father had died on Valentine’s Day.

Crowley overheard his assignment manager, Lisa Pulitzer, talking with his photographer. “His father just passed away last week,” the photographer said.

Before he could even process what the story required, a fellow reporter quietly stepped in to take the assignment, a gesture he never forgot.

Other times, it’s more complicated, says Crowley.

His father had been a police officer in Nassau County, which meant Crowley sometimes learned about crime scenes and political tensions that the public didn’t immediately see, including layoffs, arrests, and cases of public indecency.

Later, while working in Raleigh, NC as an assignment editor, police officers would occasionally pull him aside and pass along early information. One of those story ideas came in 2002. It involved an internal debate about officers moonlighting as bar bouncers in uniform on Glenwood Avenue — something Crowley heard about because a close friend owned a pub on the strip where off-duty officers worked the door.

“The chief of police called me up and said, ‘How did you find out about this? This was an interoffice meeting,” Crowley says. “I told him, ‘I’m sorry, but I can’t reveal my sources.’”

It was a moment that underscored the uneasy relationship journalists often have with law enforcement. Tips and early leads can help the public understand what happened, but they can also blur the lines between access and confidentiality. Navigating those relationships, Crowley says, required constant recalibration of what was appropriate, fair and ethical.

“Right and wrong in journalism is rarely absolute,” he says. “You’re always balancing what the public needs to know with the responsibility not to harm the people at the center of these stories.”

Joseph Saladino, supervisor of the Town of Oyster Bay in Nassau County, understands the emotional and ethical weight of journalism because he lived it long before entering public office. A former broadcast reporter who covered breaking news, such as the Challenger explosion of 1986, Saladino wrote his master’s thesis on ethics in journalism, a subject that shaped his entire approach to truth and public trust.

When journalists cover shootings, child deaths or community tragedies, the greatest ethical challenge is balancing the public’s right to know with compassion for those affected, he says.

“Reporters must tell difficult stories, but they also have a duty to protect the dignity of victims and their families.”

“When journalists lead with fairness, accuracy, and humanity,” he added, “they don’t just report the news, they protect the very trust our society is built on.”

We now live in a world where attention turns shooters into celebrities and conspiracy theorists into influencers. Unless society rethinks what it brings attention to, the harm will continue.